PETER BILL

PETER IS A SURVEYOR-TURNED JOURNALIST WHO EDITED BUILDING MAGAZINE FOR SIX YEARS IN THE NINETIES, THEN EDITED ESTATES GAZETTE FOR ELEVEN YEARS UNTIL 2009.

PETER SPENT THE PRIOR TWENTY YEARS WORKING IN CONSTRUCTION, INCLUDING A DECADE WITH HOUSEBUILDER GEORGE WIMPEY. FOR SEVEN YEARS, PETER WROTE A WEEKLY ‘ON PROPERTY’ PAGE FOR THE EVENING STANDARD. TODAY, HE WRITES A REGULAR COLUMN FOR PROPERTY WEEK.

PETER IS THE AUTHOR OF PLANET PROPERTY. HIS LATEST BOOK, BROKEN HOMES: BRITAIN’S HOUSING CRISIS; FAULTS, FACTOIDS AND FIXES IS CO-WRITTEN WITH REGENERATION EXPERT, JACKIE SADEK.

The great thing about a blog is that you can go on a bit, so I will. My morning flurry of tweets (@peterproperty) are restricted to the odd barbed comment. Attempts at building my own platform collapsed under the weight of my ignorance of WordPress.

So, to work: the stuff I will go on about a bit comes later, with a rant at the end. First, I’d like to wave the magic wand first brandished in Broken Homes, the book I co-authored with Jackie Sadek in 2020. The clue to our thinking lies in the sub-title: Britain’s Housing Crisis, Faults Factoids and Fixes. The magic wand was waved over the Fixes.

I wish:

- The grid of floor sizes laid down in the Nationally Described Space Standards were upped by 20% and made mandatory. Taking us all back to the space standards of yesteryear.

- The grid celebrating the number of rooms squeezed on every hectare in the name of sustainability to be lowered 20% to celebrate living space for families. Again, just taking us back to yesteryear.

I am aware what the above does to residual land values. The first two chapters of Broken Homes is devoted to the topic: Answer: not as much as you might think. Few give thought to the needs of families who suffer from the squeezing internal and external spaces.

No wand needed…

Now, to things that don’t need a magic wand. The first is a proposal Jackie and I put together for the Housing Finance Institute and local authority think Tank Localis, which was launched in February. You can find the whole thing here.

Briefly, the idea is to build a new generation of council homes – or Public Rental Homes (copyright P Bill & J Sadek) – led by councils, using state land and built by the suitably rewarded private sector.

To quote: ‘this is a fresh approach that will allow local authorities to provide homes which match the needs, and are within the means, of those on waiting lists. This approach involves using site-by-site appraisals that flip the present private sector appraisal methodology, which asks “what percentage of affordable homes can we afford to provide?”, to instead, “what percentage of private homes must be provided in order to produce the size and type of public rental homes (PRH) those on our waiting lists can afford?”.’

Now, to the point

Now to the substantive point, one which is beginning to gain political traction, but needs a push. The PRH idea abandons the idea of fixed percentages of ‘affordable’ homes, partly because about 80% of the homes currently defined as ‘affordable’ are no such thing for the 1.3 million households on council waiting lists.

Political unease is growing over the low number of what are becoming known as ‘truly affordable homes’.

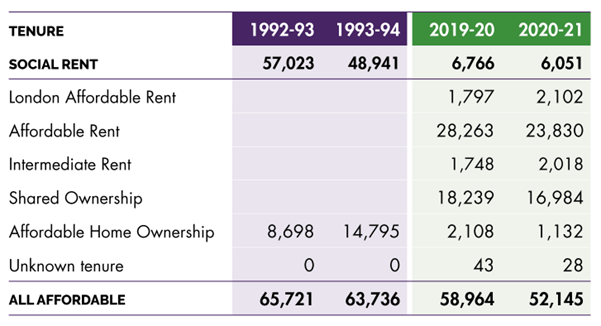

Look at the table below. We’ve gone from building nearly all affordable homes at ‘social rent’ levels to a point where less than 20% are affordable for the 6.2 million households that lie in the bottom fifth of income levels.

Don’t get me started on how many of those contain three beds or more, making them suitable for families. At a best guess it’s about 25% – or 2,000 of the 8,000 social or London Affordable Rent units build in 2020/21.

Political unease is growing over the low number of what are becoming known as ‘truly affordable homes’, meaning those rented at half local market rent or less. (In our case, meaning Public Rental Homes.)

The Levelling Up and Regeneration Bill (LURB) is currently grinding through the House of Lords. Over 500 amendments have been tabled, leading the LURB to be called a ‘Christmas tree’ Bill. Amendment 350 comes from veteran housing campaigner, Lord Richard Best. The chair of the Affordable Housing Commission is calling for 75% of money raised by a new Infrastructure Levy to be spent on affordable housing.

More pertinently, amendment 242 proposed by Lib Dem peers Dorothy Thornhill, Andrew Stunell and Kath Pinnock calls for a “comprehensive redefinition of the term ‘affordable home’ to ensure that there is a link between median incomes and the definition of affordable homes, with that definition then enshrined in regulations.”

There is an affordability crisis, not a supply crisis.

Labour agrees. “We support this proposal in principle and would want to work with the sector to ensure that there is a much more meaningful definition included in legislation and in the National Planning Policy Framework,” said Baroness Ann Taylor.

Clive Betts, the Labour MP and chair of the All-Party Housing Committee, said in The Times on April 24th that “only a significant increase in housing, particularly affordable housing, will ultimately tackle the rocketing costs of private renting that many tenants face today.”

But will this pressure turn into a rush of PRH homes or persuade councils to increase the ‘truly affordable’ element of affordable from around 20% to maybe 50% or 60%? I don’t know. But a senior figure in the private housing world said over lunch the other week: “Peter, we really do have to get back to the point where affordable means affordable.”

And, finally: the factoids that plague the sector

fac·toid [ˈfaktɔɪd]

NOUN

- an item of unreliable information that is reported and repeated so often that it becomes accepted as fact:“he addresses the facts and factoids which have buttressed the film’s legend”

What follows has been lifted bodily from Broken Homes. Numbers are a bit old; but the principles hold. At least, they do in my eyes.

But what is a ‘factoid’? Factoids were first defined by the American author of The Naked and the Dead, Norman Mailer, in his 1973 biography of Marilyn Monroe. Mailer described a factoid as an ‘item of unreliable information that is reported and repeated so often that it becomes accepted as fact’. In Mailer’s case it was something unrepeatable about the prowess of Errol Flynn.

Factoid one: Britain has a housing crisis

Emotive topic. Here are the facts.

There were 24.4 million dwellings in England on 31st March 2019, an increase of 241,000 dwellings on the same point the previous year. The number of new homes needed to absorb changes in population and changing living habits is 170,000, says the Office for National Statistics, suggesting that will bring quite enough extra homes each year between 2020 and 2040. But, of no comfort to those who cannot afford to buy or rent at market prices.

There were 88,000 families in temporary accommodation as of December 2019 and 1.15 million folks on council house waiting lists. Neither group is likely to ever have the money to either buy or rent a home at anything much above half the market rent.

For this group, there is a terrible, undeniable crisis. If you are between the age of twenty-five and forty and unable to get onto the first rung of the housing ladder, there is also a housing crisis. If prices are eighteen times the average salary, there is a housing crisis. Prices are too high.

But is the crisis the fault of housebuilders charging too much? They charge what the market bears, just like pencil-makers. The amount they charge is linked to the price of second-hand homes. Those living in second-hand homes can hardly be expected to sell at below market prices. Why should housebuilders? There is an affordability crisis, not a supply crisis.

Factoid two: building more homes will lower prices

To repeat, there were 24.4 million homes in England in 2019, 241,000 more than the year before. Might increasing the flow to 300,000 bring down prices? Unlikely: new homes are like new cars. Buyers pay more.

The price of a new home tends to lie between 15% and 20% above that of used stock. Take the argument down to the local level. Pick a town containing 50,000 homes, with an average value of £250,000 each. ‘Anytown’ adds 500 new homes in one year, adding 1% to its stock. They sell for an average of £300,000 each. On which planet would this activity lower the general price of homes? The reality is prices step up and down to the level of demand, which dances to the tune of the economy.

Might increasing the flow [of new housing] bring down prices? Unlikely: new homes are like new cars. Buyers pay more.

Factoid three: improving planning will bring forth more homes

Improvements to the planning system have never, ever contributed to more homes being built. The ‘planning system’ is like the tax system – it can always be improved. Improvements to increase the supply of land are fine and dandy. But what then gets built is an entirely separate matter.

The land banks of the top six housebuilders rose by 10,000 between 2017 and 2018 to over 350,000, despite selling over 70,000 homes at carefully controlled rates of under one per week.

As the table shows, each likes to hold four or six years of land to help plan, not to hoard.

Factoid four: prefab homes can solve the UK’s housing crisis

Prefabrication can be a good thing. The process of building components in factories has been redubbed Modern Methods of Construction (MMC): MMC is a good way of ensuring factory-standard kitchens and bathrooms. But the idea that prefabrication will ‘solve Britain’s housing crisis’ is nonsense.

Yet in early 2020, Junior Housing Minister Esther McVey was suggesting that the “industrialisation of housebuilding offers a unique opportunity to drive affordability into the sector which can then, in turn, be passed on to the house buyer.”

The misconception promoted by MMC suppliers is that because you can build faster and more cheaply, more homes will be built and sold at lower prices. Cost and efficiency savings accrue to the seller. Why on earth would they sell or rent below market price? The idea that the consumer will benefit is moonshine.

The idea that because you can build more quickly means you will sell more quickly is also a complete disconnect, as housebuilders’ steady sales rates per site per week (SPOW) rates show.

A more serious misconception put about by the promoters of prefabrication is that the public housing tenants will benefit, making affordable homes even more affordable. There may be a case that cost savings mean a social provider can build ten homes for the price of nine and they will go up a bit faster.

Granted, a benefit to the provider of homes and, OK, yes to families on the waiting list. But that still does not mean the rent the tenant pays will be less, because the house is bolted together.