PAUL SMITH

PAUL SMITH IS MANAGING DIRECTOR OF THE STRATEGIC LAND GROUP, ONE OF THE UK’S MOST SUCCESSFUL RESIDENTIAL AND RENEWABLE ENERGY LAND PROMOTERS, AND IS A DIRECTOR OF THE LAND PROMOTERS AND DEVELOPERS FEDERATION. HE IS A CHARTERED TOWN PLANNER AND A CHARTERED SURVEYOR.

PAUL BENEFITS FROM MORE THAN 17 YEARS IN SENIOR HOUSING INDUSTRY ROLES, AND IS A WELL-RESPECTED EXPERT ON HOUSING INDUSTRY ISSUES. HE REGULARLY PRODUCES LONG-FORM PIECES FOR LEADING PUBLICATIONS AND SITS ON THE ADVISORY BOARD FOR HOUSING TODAY, FOR WHICH HE WRITES A MONTHLY COLUMN.

If media reports are to be believed, Conservative MPs are joining forces to support a new planning policy requirement to include swift bricks – hollow bricks which can be used for nesting – in all new houses. It is a shame they aren’t displaying the same focus when it comes to building new homes for people.

In theory, at least, their manifesto commitment to deliver 300,000 new homes each year remains – a target we’re currently missing by around 25%. That figure should be seen as the absolute bare minimum if we are to address the housing supply crisis and all its associated ills. We have fewer homes per capita than almost every other developed country – and 25% fewer than economically and demographically similar France – a result of being out-built by those other countries in the 75 years since our current planning system was introduced.

Nothing…

The government’s actions, however, tell us they don’t really think reaching even 300,000 homes a year is that important. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has repeatedly avoided re-committing to the target, while housing secretary Michael Gove consulted on a series of reforms to the planning system before Christmas which are likely to push housing delivery in the opposite direction.

If the proposals come into force, planning to deliver the number of new homes required by the standard method will become optional for local authorities. The standard method itself will be downgraded to an “advisory starting-point” while councils will only be required to plan for “as much housing need as possible,” rather than working out how to meet need in its entirety.

The changes would also see the requirement to maintain a five-year supply of deliverable housing land watered down to the point of being largely irrelevant. This is currently a key part of monitoring the performance of local plans, ensuring councils estimate future delivery and take pre-emptive action to stop the supply of new homes falling too far.

Lichfields predict that these amendments could see delivery drop to as little as 156,000 new homes each year.

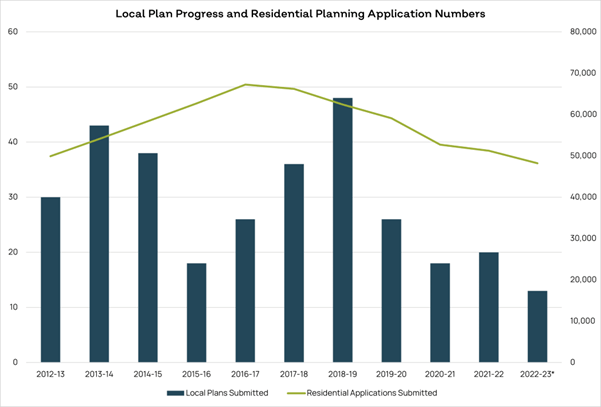

Even before these mooted changes, the supply of development sites was already coming under pressure. Faced with the continual promise of systemic reform, the number of new Local Plans being adopted has declined for each of the last five years. Partly in consequence, the number of applications for new homes has fallen for each of the last six years too. Research by Savills has shown that even the biggest PLCs are operating from fewer sales outlets than they were just five years ago – and almost 25% fewer than they were before the 2007 financial crisis.

…nowhere…

The government’s increasing coyness about how many homes we should be planning to deliver is accompanied by increasingly strident assertions about where they should – or more accurately should not – be built.

Our towns and cities won’t be expected to grow outwards. Gove’s proposed reforms to national policy explain that local authorities will not be expected to release areas of green belt for development simply in order to meet housing targets.

Nor are the government overly keen on our urban areas growing upwards. A further proposed policy change allows councils to under-deliver new homes if meeting need would mean building at densities which are out of character with the existing area.

If we can’t build up or out, the only remaining option for meeting housing need is to ask a neighbouring local authority to help out. The mechanism for doing that – known as the duty to cooperate – is to be abolished and replaced with an “alignment test.” However, the government doesn’t yet know what this will be and whether it will even relate to housing at all.

Whilst it seems the government isn’t keen to plan for new homes, it nevertheless wants them built at warp speed

This is all compounded by the many “neutralities.” Nutrient neutrality – effectively blocking new homes in river catchments across the country because of their potential impact on protected habitats – is currently holding up around 120,000 new homes. A recent court judgement even prevents some planning conditions being discharged on already approved schemes. That’s despite new homes having a very small impact on the nitrate and phosphate pollution that is of particular concern – agricultural fertilisers and sewage works in urgent need of improvement are by far the biggest contributors. While the government is now making noises about removing this particular barrier to development, their response has been slow – the issue first arose almost three years ago.

Neutrality doesn’t just apply to nutrients. Water neutrality – a requirement for new homes not to increase demand for new drinking water – is stopping new homes being built in some parts of the country, despite it having been more almost 35 years since a new reservoir was built in England.

And it’s also about “recreation neutrality.” For example, developers of new sites within a 12.6 kilometre radius of the Chilterns Beechwoods Special Area of Conservation are being asked to pay a combined £18.2 million to the National Trust, who own the site, to help mitigate the effects of the anticipated increase in visitor numbers. There is no sign of the National Trust being asked to close the on-site café they opened recently though.

All in all, there aren’t many areas which the government doesn’t apparently consider to be unsuitable for development.

…all at once

Whilst there is little sign of decisive action to help increase the flow of development sites, the government is taking steps to try to pin the blame for the housing supply crisis on developers. They have already consulted on a series of potential policy changes aimed at forcing developers to build homes more quickly and have said they plan to introduce financial penalties for developers who don’t. At the behest of Gove, the Competition and Market’s Authority are also investigating the housebuilding industry for evidence of land banking. Whilst it seems the government isn’t keen to plan for new homes, it nevertheless wants them built at warp speed.

Over the last twenty years, there have been four independent reviews into land banking claims, an Office of Fair Trading investigation and a data review by the civil service. None found evidence that developers deliberately withhold new homes from the market. That should surprise no one as it would be economically illogical. House prices are set by the 80% of transactions in the second market, not new build developers. Even the biggest house builders complete fewer than 10% of all new build homes each year, insufficient to influence prices even if they wanted to. Even with rapidly rising land values, the best way for developers to maximise their return on capital – the key financial metric for them – is to build and sell homes as quickly as the local market is able to absorb them, not to sit on land and accrue interest charges.

The results of the government’s approach to house building are all too predictable – fewer homes are being granted planning permission, and fewer new homes are being built. Some SME developers – which the government claims to be central to its housing policy – are giving up altogether and closing down.

If your housing strategy is to build nothing, nowhere, all at once, then that is exactly what you will get.